SYMPTOM CHECKER

CONDITIONS

Male

Female

Child

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Legs & Feet Concerns

Dental & Mouth Concerns

Ear & Nose

Eye Conditions

Head Conditions

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Legs & Feet Concerns

Front

Back

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Dental & Mouth Concerns

Ear & Nose

Eye Conditions

Head Conditions

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Dental & Mouth Concerns

Ear & Nose

Eye Conditions

Head Conditions

Front

Back

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Neck Links

Head & Neck Concerns

Arm, Hand & Shoulder Concerns

Neck Links

Head & Neck Concerns

Front

Back

Online Clinic

Wise Healthcare

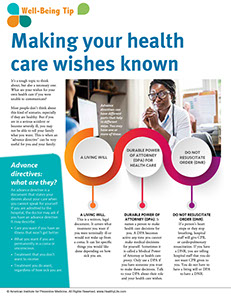

Making your health care wishes known

Print on Demand

It’s a tough topic to think about, but also a necessary one. What are your wishes for your own health care if you were unable to communicate?

Most people don’t think about this kind of scenario, especially if they are healthy. But if you are in a serious accident or become severely ill, you may not be able to tell your family what you want. This is when an "advance directive" can be very useful for you and your family.

Advance directives: what are they?

An advance directive is a document that states your desires about your care when you cannot speak for yourself. If you are admitted to the hospital, the doctor may ask if you have an advance directive. It may describe:

• Care you want if you have an illness that won’t get better.

• What you want if you are permanently in a coma or unconscious.

• Treatment that you don’t want to receive.

• Treatment you do want, regardless of how sick you are.

Advance directives can have different parts that help in different ways. You may have one or more of these:

• A living will. This is a written, legal document. It covers what treatment you want if you were terminally ill or would not wake up from a coma. It can list specific things you would like done depending on how sick you are.

• Durable power of attorney (DPA). It names a person to make health care decisions for you. A DPA becomes active any time you cannot make medical decisions for yourself. Sometimes it is called a Medical Power of Attorney or health care proxy. Only use a DPA if you have someone you trust to make these decisions. Talk to your DPA about their role and your health care wishes.

• Do not resuscitate order (DNR). If a person’s heart stops or they stop breathing, hospital staff will give CPR, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation. If you have a DNR, you are telling hospital staff that you do not want CPR given to you. You do not have to have a living will or DPA to have a DNR.

Some states do not consider living wills or DPAs to be official legal documents. Even if it’s not legal, an advance directive or DPA can be very helpful. It can help your family and/or doctor make decisions you want so you get the care you desire. Your doctor or an attorney can tell you about your state's laws. All states recognize and honor DNR orders that are in a patient’s medical record. An attorney does not have to do a DPA or living will. Many people fill them out themselves.

What do I put in an advance directive?

If you’re thinking about getting an advance directive, you may be wondering what it should say. Your doctor or an attorney can help you, and you may want to think about it for a while.

Health care items that are often listed in a living will include:

• Ventilation (artificial breathing machines)

• Dialysis (machines that work for kidneys that are failing)

• Tube feeding (used when a person cannot eat or drink)

• Palliative care (care that keeps you comfortable, such as pain relief measures)

• Organ donation or donating organs to be used for research

Why do I need an advance directive?

Most medical experts agree that an advance directive is helpful. It makes your preferences about medical care known before you become sick or injured. It means your loved ones will not have to make hard decisions about your care while you are sick.

An advance directive can give you peace of mind. If you feel strongly about receiving certain treatments, an advance directive helps ensure that your wishes will be honored. It gives you more control over your own health care.

Where do I start?

An advance directive doesn’t have to be hard. It can be short and simple. You can:

• Get a form from your doctor.

• Write down your own wishes yourself.

• Discuss your wishes with your DPA.

• Meet with an attorney to write an advance directive.

• Get a form from your local health department or Area Agency on Aging in your area.

It’s a good idea to have your doctor or an attorney look at your advance directive. This ensures your wishes are in line with state laws. It also gives you a chance to answer questions and make sure your wishes are understood. When you are done, have your advance directive notarized. Give copies to your family and your doctor.

You can change or cancel your advance directive. This can be done when you are of “sound mind,” which means you are able to think and communicate clearly. Any changes you make must be signed and notarized according to the laws in your state. Make sure that your doctor and family members know about the changes.

Sources: Medicare.gov, American Academy of Family Physicians

This website is not meant to substitute for expert medical advice or treatment. Follow your doctor’s or health care provider’s advice if it differs from what is given in this guide.

The American Institute for Preventive Medicine (AIPM) is not responsible for the availability or content of external sites, nor does AIPM endorse them. Also, it is the responsibility of the user to examine the copyright and licensing restrictions of external pages and to secure all necessary permission.

The content on this website is proprietary. You may not modify, copy, reproduce, republish, upload, post, transmit, or distribute, in any manner, the material on the website without the written permission of AIPM.

2021 © American Institute for Preventive Medicine - All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer | www.HealthyLife.com